Lt. Howard Vander Beek, a small-town boy from Iowa, gripped the wooden wheel of his 56’ metal craft, leaned forward, and stared into the no-moon-black storm-tossed sea. The swells rolled, and wind driven spray stung his face as he battled the elements to guide an armada of 865 ships onto Utah Beach. It was Tuesday, June 6, 1944. D-Day.

The young Lieutenant felt both fear and confidence given that for months he and his crew of fourteen had trained and practiced for this very moment. Their particular role, though, had been a carefully guarded secret until just a week ago even from the ships that followed in their wake. Since the evacuation at Dunkirk four years and two days ago, the Axis knew there would be an invasion aimed at freeing Europe. To lead that charge, the Allies had devised an intricate plan that accounted for every probability and yet, the success of which was at the mercy of all of the things that can go wrong in the fog of war.

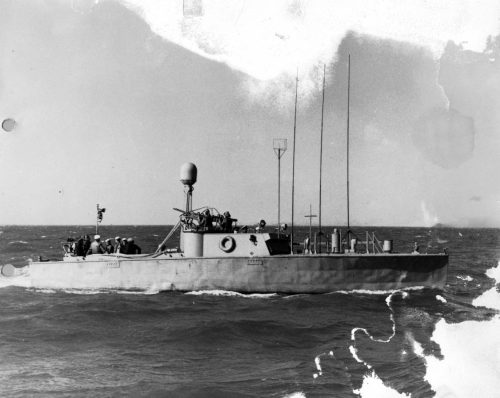

The fleet grey hull that rolled beneath the helmsman’s feet was just as special as the men selected for this mission. She was built specifically to quickly locate mines and obstacles the Germans had littered the shore with. To do that, the vessel was equipped with the latest radar, sonar and communications technology. Each man tasked with operating those devices were trained, tested and tried and had proven their skills. The Lieutenant? He was already battle-hardened at the invasion of Sicily where he served with the Raiders and Scouts, the predecessors of the Navy Seals.

Just as the pre-dawn, pale grey coast of France began to emerge the heavy cruisers that lay close behind split the cool morning air with thunderous salvos. The armada stood so near to shore that the trajectory of their fourteen-inch, sixteen-hundred-pound shells, created a blast of wind that rocked Beek’s boat as they soared over head and even cause those aboard to involuntarily duck.

The bloody barrage on the fortifications had barely halted when suddenly the sky filled with swarms of bombers that dropped a deluge of steel and death. That was the signal all had awaited.

The designation of the Lieutenant’s boat was Landing Craft, Control which clearly explained its purpose. In addition, three more boats, just like his, were lined out abreast, each assigned to clear a path for the men and equipment that would storm the beach. As they began their perilous trek, first one, then another, and finally the third LCC evaporated into an explosion of water and debris as they struck mine after mine after mine.

Unsure how to proceed, chaos and hesitance gripped the floating army and the success of the entire mission hung in the balance. Then, Lt. Beek’s bullhorn began to bark out orders. Racing back and forth between the columns of landing craft, he dashed through the spray and raced ahead to bring wave after of wave of troops and tanks ashore. In the next seven and a half hours, he and his men had led nineteen assaults.

For the next few weeks the crew lived on C-rations and took turns catching a nap when they could on LCC-60’s two cots. When things had finally settled down somewhat, Lt. Beek, replaced the ship’s wind tattered, powder and diesel stained ensign and noticed the symmetrical hole left by a German machine gun round. He carefully placed the folded banner in his locker. At war’s end, the first American flag to reach the shore of Europe was respectfully hung on the wall of his home.

Civilian Howard Vander Beek, went on to become a distinguished professor of English and wrote a moving and detailed account in 1995 entitled Aboard LCC 60: Normandy and Southern France, 1944. When he passed away in 2014, he was 97 and the historic relic became part of his estate. Two years later it was purchased by a Dutch collector for $514,000 who intends to donate it to the American people in appreciation for liberating his country.

In the six months leading up to D-Day, the Charleston Naval Shipyard built twenty-four Landing Craft, Control. At that time, due to the rush to complete these vessels, many of the normal record-keeping practices were understandably not adhered to. An extensive search of files has failed to find documentation that any other shipyard built that type of craft. Given that LCC-60 went on the participate in the invasion of Southern France and in the Pacific Theater of Operations, it appears unlikely that the Navy had an abundance of such ships. Whether our workers fabricated her, it’s hard to say. Regardless, the builders, the ship, the men and the flag reflect all that is America.